With electric vehicles becoming more mainstream with every passing year, many consumers considering alternate power are faced with a dilemma: Do I go plug-in hybrid (PHEV) or go all-in and pure electric (EV). The difference is PHEVs run on electricity for a short distance before switching to a blended gas/electric hybrid mode; EVs run exclusively on electricity.

Ultimately, the goal is zero tailpipe emissions, so while PHEVs have and will continue to provide a valuable stop-gap solution, eventually they will make way for the pure EV. For now, however, the modern PHEV is making a very strong case for itself — for example, the fastest Toyota RAV4 ever produced is the plug-in Prime!

2022 Toyota RAV4 Prime

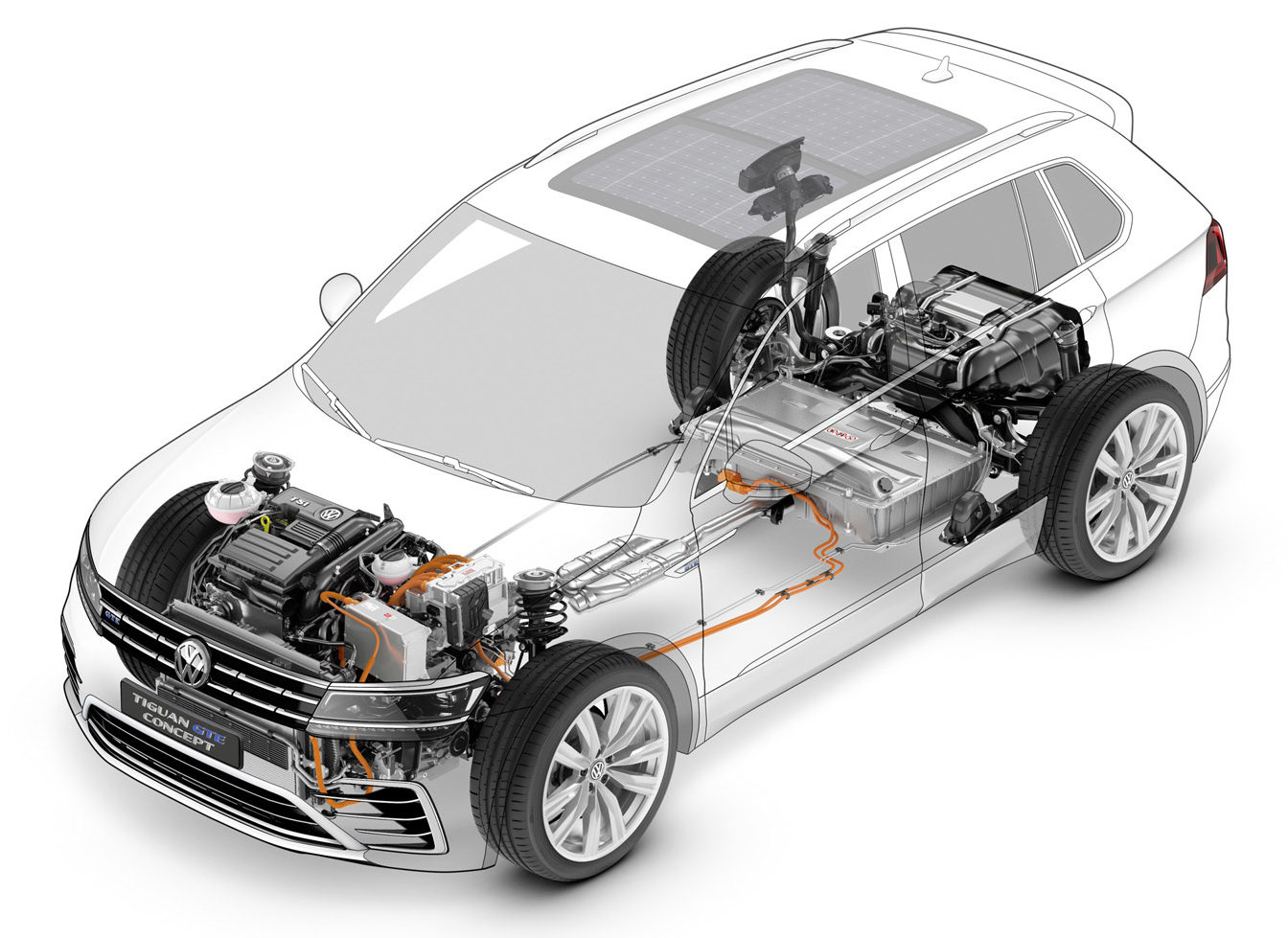

It’s important not to confuse a PHEV with a regular hybrid. While the two share much of the same technology under the hood, the non-plug-in hybrid uses a much smaller battery with the average coming in at around 1.3 kilowatt/hours. These batteries really only have enough power to deliver electric assistance and very little, if any, electric-only driving. Plug-in hybrids, on the other hand, use a significantly larger battery. Today, the average PHEV has a battery that’s rated at around 15 kW/h.

The key is the larger battery is capable of delivering an electric-only driving range. It does vary by manufacturer and battery size, but in general they can deliver between 50 and 60 kilometres of electric-only driving. Once the battery has been used up, the vehicle continues to operate as hybrid. Now, the engine and regen braking return some power to the battery so it operates like a regular hybrid with the electric side providing assist when possible.

Volkswagen Tiguan Hybrid concept

According to Statistics Canada, for those with a long commute by car, the average one-way commute is 57 kilometres. As such, many PHEVs have the wherewithal to do most of the route without burning any gasoline. Those lucky enough to have a power outlet at work can do the round trip without breaking a sweat! The bottom line is when a PHEV is charged regularly the overall cost of ownership drops dramatically. The annual fuel cost for the gas-powered Hyundai Tucson is $1,800 based on 20,000-km/year compared with $994 for the Tucson PHEV. These numbers speak volumes.

Another plus is PHEVs are faster to charge than an EV because of the battery size. The Hyundai Tucson PHEV has 13.8 kW/h battery that takes 1.7-hours to charge using a Level 2 outlet. This coupled with the gasoline side also means taking a long trip is no different to making the same trip in a regular gas-only vehicle — it just costs less on average.

Hyundai Tucson PHEV

Finally, the upfront purchase price of a PHEV is lower than an EV. The downside is you still have the same cost of maintenance as a regular non-hybrid model and the cost of gasoline when the PHEV reverts to hybrid operation.

The key advantage to an EV, aside from its zero local emissions and the fact it gets a larger rebate, is the inherent performance at play — the instant-on nature of the torque delivers sharp acceleration, so an EV blasts off the line and on to speed effortlessly. And with hydroelectricity so prevalent in BC, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador and Yukon, battery power for PHEVs in these provinces especially is truly emissions free.

Another big EV advantage is the cost of “fuel.” While a PHEV is much cheaper to operate than its gas-powered sibling, EVs are, on average, almost half as much again. The Kia EV6 with the extended-range battery and all-wheel-drive is about the same size as the Tucson PHEV, yet it has an annual electricity cost of just $597.

Kia EV6

Another plus for EVs is there really is no scheduled maintenance, so this cost goes by the wayside, as does much of the cost associated with brake repair. With regen braking doing the vast majority of the slowing, the regular brakes do very little work. Porsche says the Taycan’s brakes only need replacing once every six years!

In the past, part of the reason for the hesitancy to invest in an EV boiled down to range anxiety. In the early days, the limited range and limited availability to charge the vehicle when on the road made anxiety was a very real concern. However, the driving range offered by today’s EV has improved enormously, as has the infrastructure. In short, the hassles that defined yesterday are all but gone today.

Genesis GV60

The Genesis GV60 has a driving range of around 420 km and it can be charged from 10 per cent to 80 per cent in 18 minutes when plugged into a 350-kW DC fast charger. While still not the equal of pumping a tank of gas, the difference is narrowing all the time. Moving forward, lighter and faster-charging batteries and an expanded DC fast charger network will eventually see the EV become a user-friendly alternative to gasoline.

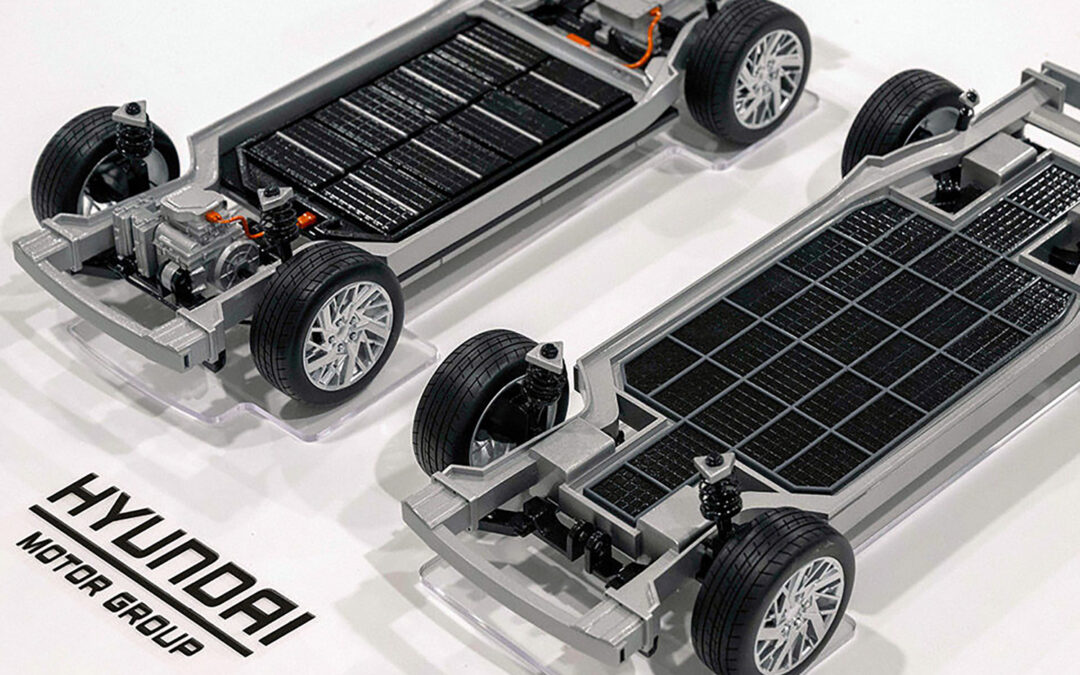

The good news is both the PHEV and EV choices are growing almost daily. The range runs from small hatchbacks, through the mid-range and on to the luxury vehicles. While all PHEVs and some EVs like the BMW i40 M50 share their platform with their gas-powered counterpart the trend is to optimize the EV by basing it on a dedicated electric platform — the Mustang Mach E rides on Ford’s Global Electrified 1 platform, for example.

Charging the 2022 Ford Mach-E GT at the PetroCanada fast charger near Alliston, ON

At this point, choosing between a PHEV and an EV really boils down to the driving situation and upfront cost. PHEVs are more affordable and have an edge if longer trips are the norm; EVs are cleaner and cost less to operate. They also bring grace and pace to the driving experience.