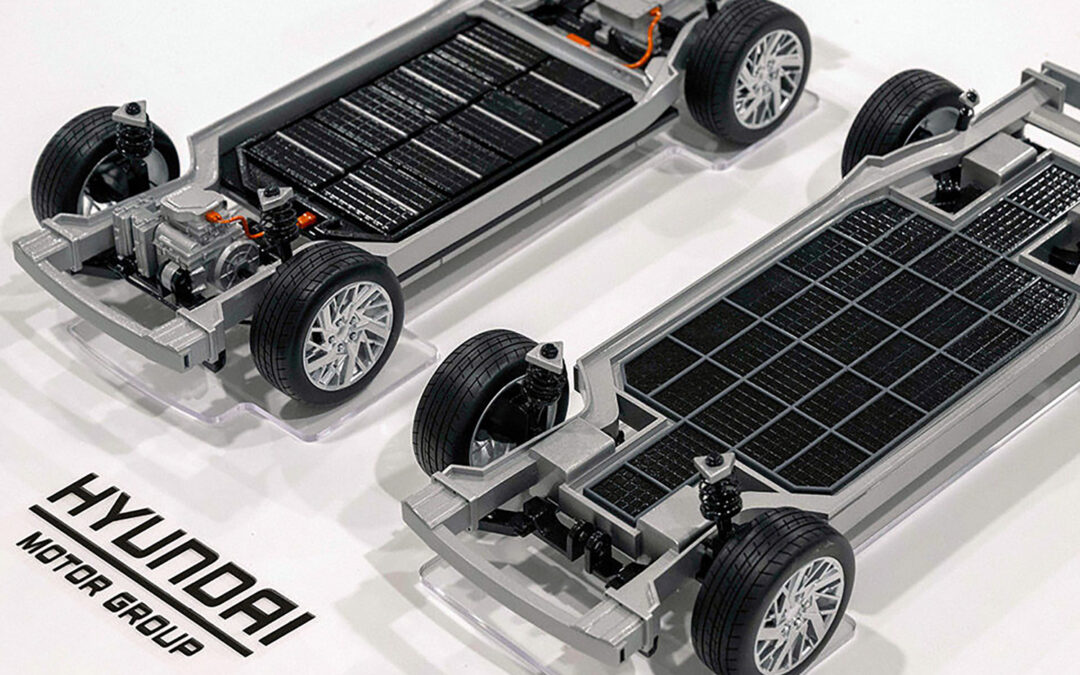

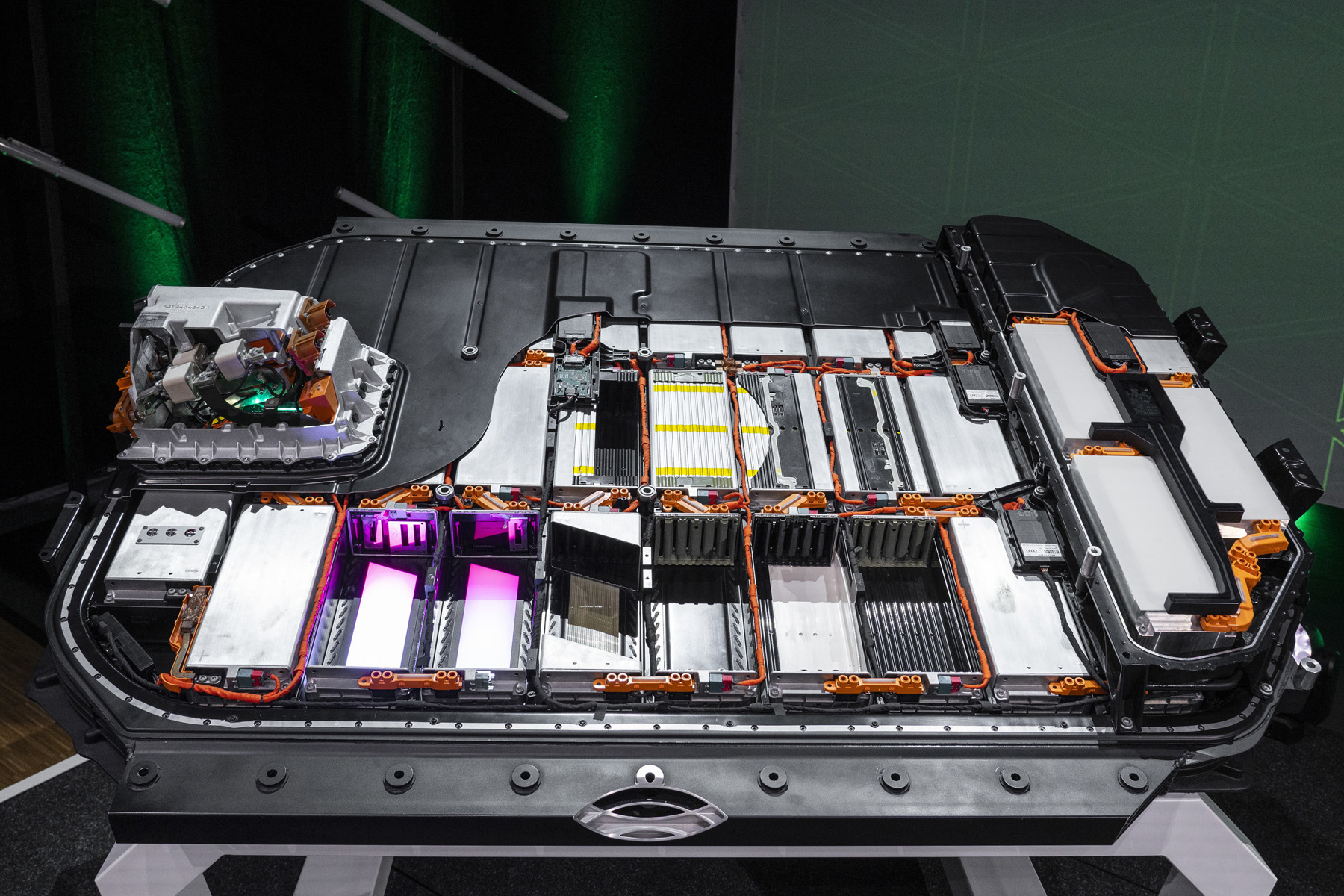

Lift the lid of an EV battery pack and you’ll find hundreds, if not thousands, of individual cells organized into modules that are linked together to deliver the rated capacity — it is the modular concept that allows one casing to accommodate batteries of differing capacities. The problem is ramming a charge into any battery will cause it to overheat and repeated overheating causes damage. This is the why it takes time to recharge an EV’s battery. It needs to be done at a rate that will not cause heat-related deterioration.

All EVs have a sophisticated ‘brain’ that oversees the rate at which the battery is charged. The goal is to mitigate these heat-related issues. When the charger cable is plugged into the EV, the two do a handshake to agree on the charging parameters.

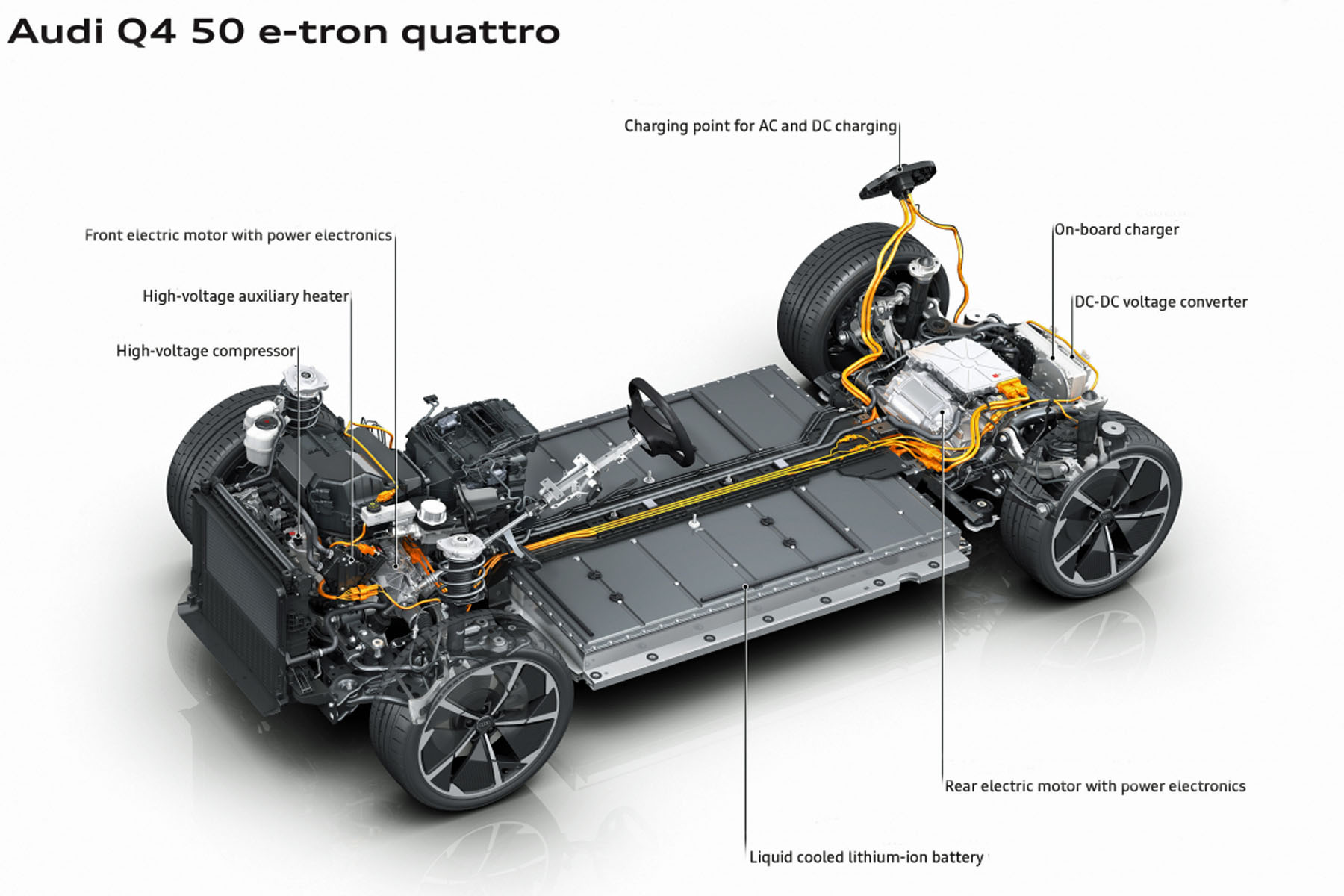

Cutaway of an Audi e-tron

The reasons for the variation in charge time is down to a number of factors. Some are seemingly innocuous, like the ambient temperature and the temperature of the battery. Very hot or cold temperatures will slow the process; a warm battery tends to accept a faster charge than a cold one — around 30C is ideal. More importantly, it boils down to the battery’s size, the acceptance rate of the battery measured in kilowatts (kW) and the state of charge (SoC) when the charging begins.

Looking at the VW ID.4 gives an insight. It has an 82 kW/h battery and an acceptance rate of 125 kW. Plugging it into a fast charger rated at 150 kW or more when the battery is at a 5 per cent SoC will see it reach its 125 kW peak charge rate quickly. It maintains this charge level until it hits about a 30 per cent SoC. Now, it reduces the charge rate to around 100 kW and when the battery hits a 60 per cent SoC it will be charging at around 80 kW. The gradual reduction of the charge rate is needed to prevent the battery from losing its cool.

A cutaway of an Audi battery pack

The watershed arrives when the battery reaches an 80 per cent SoC. Now the charge rate drops off significantly, so it takes a much longer time to go from 80 per cent to fully charged, even when using a fast charger. It’s not by coincidence this is why manufacturers quote the fast charge time as being to the 80 per cent mark. For the most part, the final part of the charging cycle is best done using a Level 2 charger. It can be likened to a slower trickle charge, so the battery does not overheat as it nears capacity.

Beyond the tail-off of the charge, the rating of the fast charger also has a big effect. If the fast charger delivers less power than the EV’s acceptance rate the charger is the limiting factor. Conversely, if the EV’s acceptance rate is lower than the charging station’s output, the EV becomes the limiting factor.

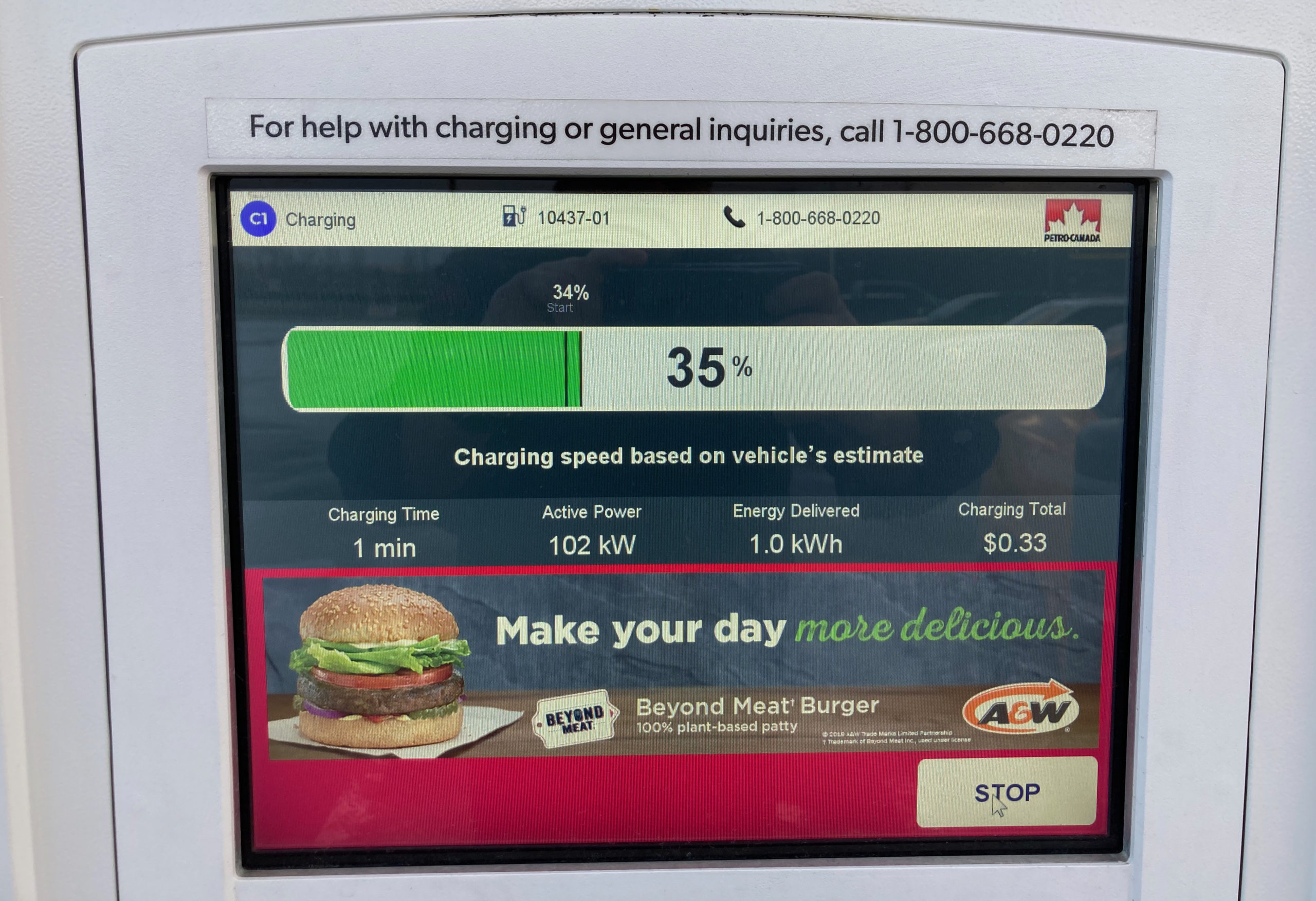

A PetroCanada DC Level 3 charger

The Audi e-tron GT has a 93.4-kW/h battery and an acceptance rating of up to a 270 kW. This high acceptance rate is down to its 800-volt architecture and the elaborate cooling systems. Plugging it into a 350 kW fast-charger will see the GT reach an 80 per cent SoC in around 25 minutes. However, using a 100 kW fast charger ups the charge time to around 50 mins. Here in Canada, many of the fast chargers are limited to 50 kW. This will leave the driver sitting around for over an hour.

Fast charging certainly has convenience on its side, even if it’s only for a ‘splash-and-go’ stop. However, as with just about everything in life, convenience comes at a price. Depending on the network it can cost up to $20/hour and, in some cases, there are parking fees on top of that cost!

Read more: How battery pre-conditioning saves your EV range

The limitations that apply to Level 2 chargers are less because the heat factor is much lower, however, the time needed to replenish the electrons is significantly longer. A typical 7.7-kW Level 2 home charger will take 12 hours to completely charge the e-tron GT’s battery. The longer Level 2 charge time does, however, significantly reduce the cost of charging and overall operating cost.

Natural Resources Canada’s Fuel Consumption Guide says the VW ID.4 has an annual ‘refuelling’ cost of $606; the Audi e-tron GT is $768/year. These costs are based on driving 20,000 kilometres a year and a $0.15/kWh electricity cost. The reality is electricity costs are greater that this, but these numbers do give a good idea of the relative costs when comparing different EVs.

The other issue facing any EV is repeated charging also causes the battery to degrade. How many cycles (defined as the complete charge and discharge of the battery) an EV battery is capable of being subjected to before any loss in performance is open to debate. However, the consensus seems to be around 1,500 charge cycles. To mitigate the degradation caused by constant cycling the battery’s management system prevents the EV’s battery from ever being fully charged or completely discharged. The good news is the cycle-related degradation is not happening as quickly as originally thought, so it is taking a lot longer for the owner to see any real loss of performance.

Moving forward the so-called “solid-state” battery, which is beginning to loom ever larger, will address both the charge time and cycle-related deterioration. Rather than using a liquid electrolyte it uses a solid electrolyte. This allows it to accept an 80 per cent charge in just 15 minutes. More importantly, a solid-state battery has the potential to retain 90 per cent of its capacity even after 5,000 charging cycles. Now that would make gasoline redundant in a hurry!