The much-heralded Hydrogen Era was once a very hot topic. The hype around it moved Mercedes-Benz to drive three B-Class F-Cells, a fuel cell-powered electric vehicle (FCEV), 30,000-kilometres around the world to prove its viability.

That, however, was way back in 2011. Since then, thanks to the popularity of battery-powered electric vehicles (BEVs) and the success of Tesla, Mercedes announced it will no longer invest in FCEVs, at least not for the passenger car market. The same seems to apply to many of the major players.

Mercedes-Benz F-CELL

The argument to use the most abundant natural renewable resource on the planet as a fuel, however, is very strong. The current crop of gasoline-powered passenger cars account for 12 per cent of the total greenhouse gas emissions; coal-fired electricity generation pumps almost three times the that amount into the air (30 per cent). This means that while a BEV represents a “zero local emissions” solution, its effect on air quality amounts to little if the electricity needed to recharge the battery comes from a dirty resource.

If you compare the electric Nissan Leaf with the gas-powered Sentra, two similarly-sized cars, the relative cleanliness of each varies according to where it’s being driven. In Norway, the Leaf is five times cleaner than the Sentra. In Canada, the two are roughly equal in terms of overall emissions. In China, the Leaf is five times dirtier than the Sentra.

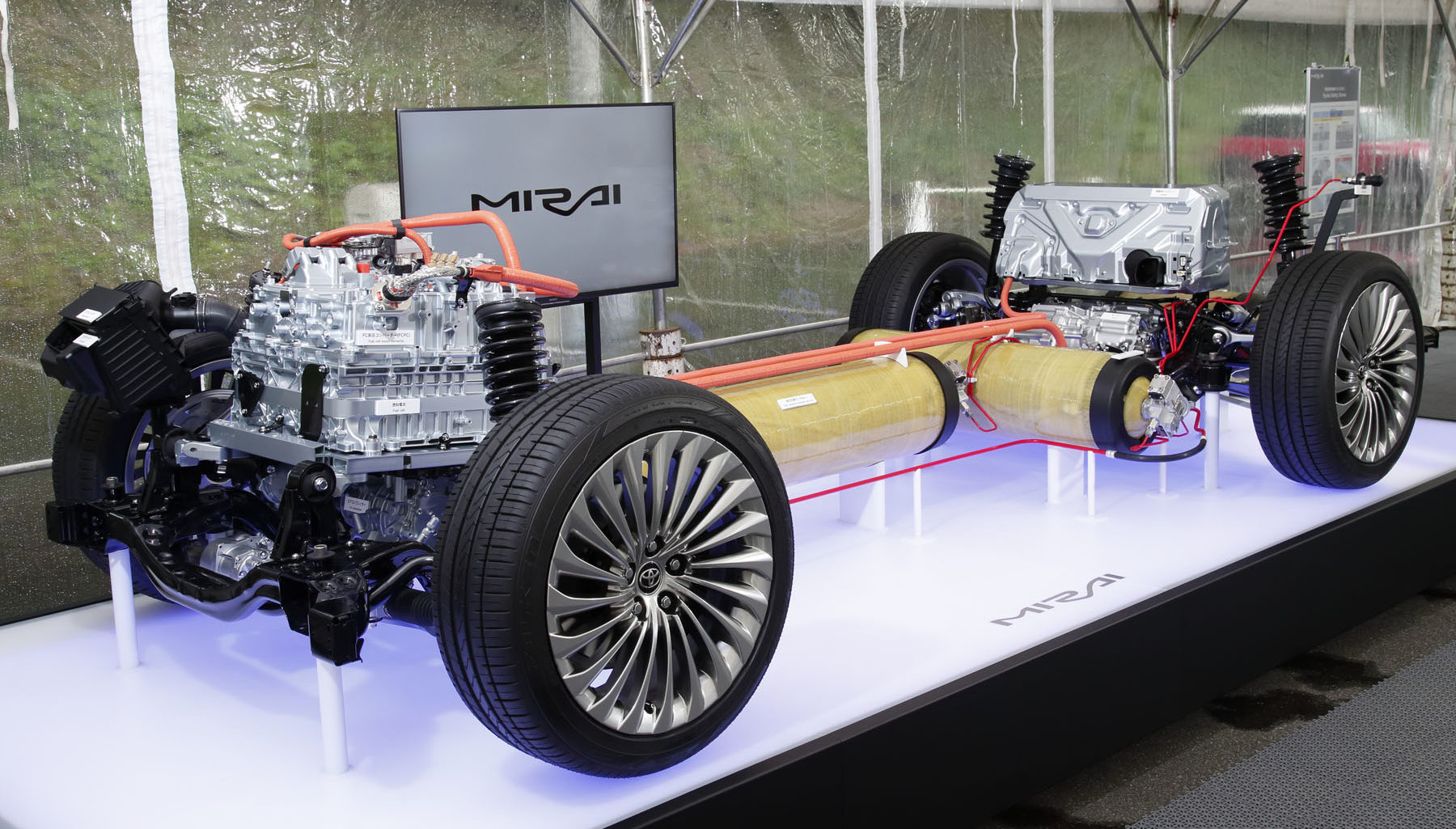

Toyota Mirai FCEV

It boils down to the manner in which the electricity is generated. In Norway, it’s all clean hydroelectric generation. In Canada, it is a mix of nuclear, natural gas, coal and hydroelectric, so much of the good is cancelled out by the emissions of the bad, and some of the coal-fired generating stations across Canada are slated to stay online until 2030. In an ironic twist, the Canadian government wants at least 60 per cent of new light-vehicles sales to be zero-emission by then and 100 per cent by 2035.

In China, the vast majority of power generation is done with coal. In 2021, 58 per cent of the country’s total energy consumption was supplied by coal, which helps to explain why China contributes 28 per cent of the world’s carbon-dioxide emissions.

Hyundai Nexo FCEV

Now this is not to bash the current range of BEVs, but rather to point out that until electricity comes from clean, renewable resources the improvement in air quality will remain relatively small. This is also true of hydrogen, as it must come from the same clean resources.

However, where the FCEV comes into its own is the fact it can deliver a longer driving range, it has a refuelling time that’s very close to that of pumping a tank of gasoline and it leaves a smaller carbon footprint than a BEV. The only by-products are water and purified air, and there’s no lithium ion battery to deal with at the end of its useful life (or a very small battery, at most). Hydrogen also has energy density on its side. One kilogram of hydrogen has the same energy as 2.8 kg of gasoline. However, the biggest benefit is the fact an FCEV delivers uncompromised performance and range in cold climates.

Cutaway of a Toyota Mirai FCEV

Any BEV loses driving range in winter, especially because of the need for the battery to power ancillaries other than the electric motor(s). On a cold and wet night, the list runs from the lights, wipers and, potentially, heated rear window to the need to keep the riders warm. How much the range drops is open for debate. The Norwegian Automobile Federation says it drops by 20 per cent; the AAA in the US says this number can soar to “41 per cent with the heater on full blast.” Practical experience has shown the likes of the Ford Mustang Mach-E and Hyundai Ioniq/Kia EV6 can lose more than 100 km of driving range when the mercury plummets to -10C.

The fuel cell is far from new. In 1842, William Grove produced a “gas battery.” He used reverse electrolysis to combine oxygen and hydrogen to produce water and electricity. In spite of this masterful invention, it went nowhere because this new-fangled power source called gasoline was getting ready to muscle its way in and go on to become the dominant fuel for the next 136 years. The fuel cell did make a comeback thanks to NASA — the astronauts needed power and drinking water. The fuel cell delivered both.

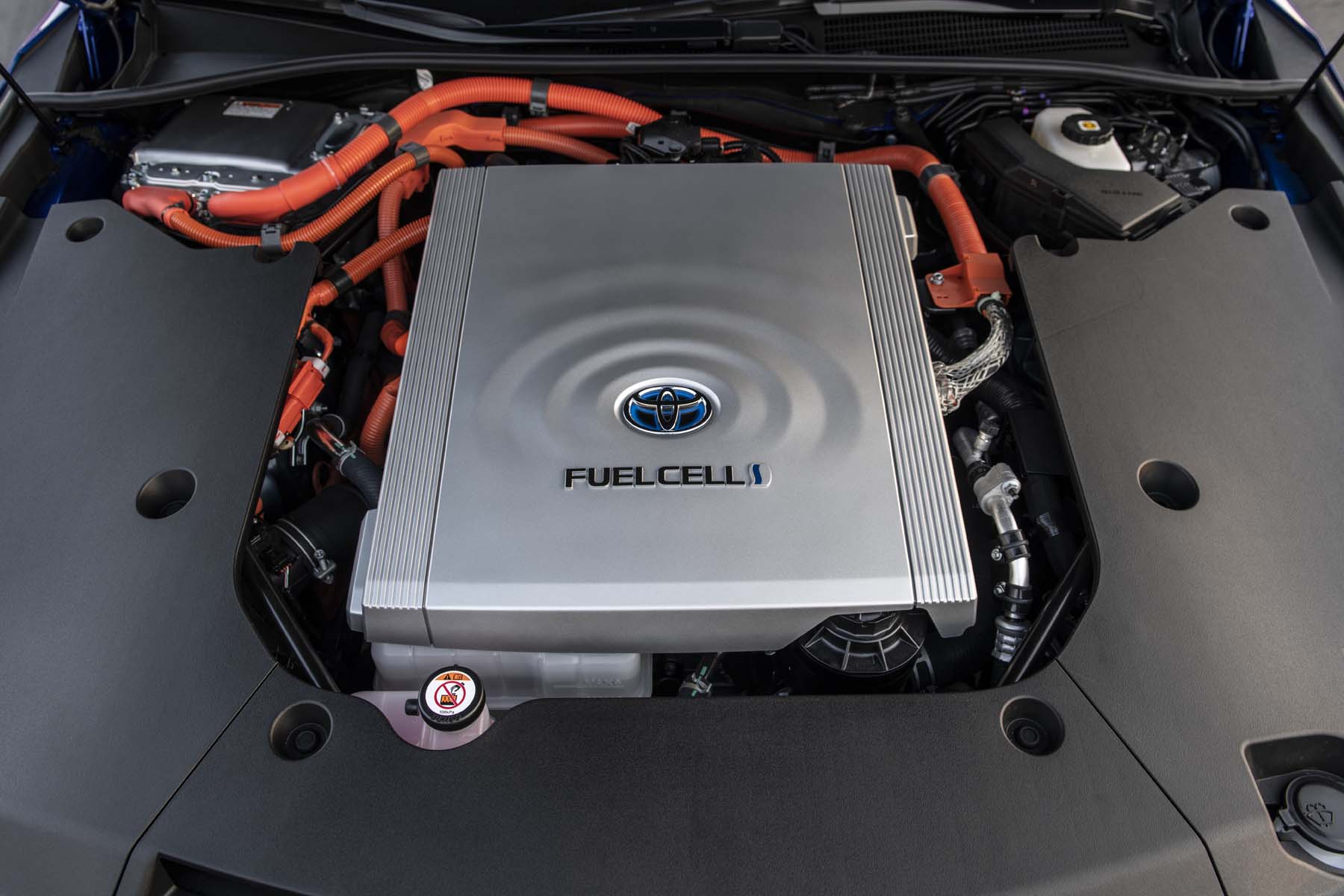

2022 Toyota Mirai / Neil Vorano, The Charge

The FCEV’s stumbling block is very simple — there is virtually nowhere to refuel. In California, then-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger was pushing the so-called Hydrogen Highway. His contention was it would give those with hydrogen-powered vehicles a viable refuelling infrastructure. According to the California Fuel Cell Partnership there are still only 53 hydrogen refuelling stations in the state. In contrast, there were 8,269 gasoline stations in 2019. The silver lining is another nine hydrogen stations are under construction and 162 more are planned.

In Canada, then British Columbia Premier Gordon Campbell announced plans for a string of public hydrogen refuelling stations between Vancouver and Whistler. It was part of a master plan that would help to make the 2010 Winter Olympics the most sustainable ever! Fast-forward to today, and there are only five public hydrogen refuelling stations in BC. The truly sad part is the fact there are only two stations to be found throughout the rest of the Canada — one in Mississauga and one in Quebec City. Again, by way of reference, there were 11,908 retail gasoline stations in Canada in 2020, according to the Canadian Fuels Association.

Toyota Mirai FCEV

The irony here is Canada is one of the top 10 hydrogen producers in the world today. The plan is to leverage this position moving forward. The Hydrogen Strategy For Canada, a report released in December 2020, predicts that by 2050 there will be some five million FCEVs on the road and they will be supported by a nationwide refuelling infrastructure. Good luck with that one! Right now, there are only two FCEVs sold in Canada — the Hyundai Nexo and Toyota Mirai.

As it stands, there are roughly 200 FCEVs on Canadian roads, which is a non-existent number when compared to the roughly 24-million light-duty vehicles on the road across the country. Simply stated, until the number of FCEVs grows the infrastructure will not, and until the infrastructure becomes viable where’s the incentive to use the most abundant natural resource on the planet as a fuel?